Digital Writing Assistants for Expert Witnesses

By Noah Bolmer

Expert witness reports must be informative, concise, and well-written. Seemingly minor grammar mistakes or unclear synthesis can alter the meaning of your text, which can be exploited by opposing counsel. When word processors alone won’t cut it, consider these tools for improving your expert witness reports.

Please note: Some of these tools have AI components. We are not AI-system experts, and the ways these systems work are changing rapidly. You should review how they handle information you input into the system before use (as well as the usual privacy information), and note that prices are at the time the reviews were written.

Writing Assistant vs. Word Processor

Word processors such as Microsoft Word and Google Docs are the workhorses of document writing, with tools enabling a tidy layout, proper punctuation, and spellcheck. While word processors have evolved over the years to include grammar checking and writing analysis, their built-in tools are less powerful and complete than purpose-built software. With the promise of tone, style, and structure improvements, I’ve evaluated four popular writing assistants for expert report writing.

Factors

In choosing a writing assistant, there are four important factors:

- Price: Cost runs the gamut, from completely free, to subscription-based “SAAS” (software as a service) models. While many software companies have attractive offers to get started, it is best to compare subscription pricing using the post-offer monthly rates, which can be hidden. All subscription plans feature annual rates for additional savings, but I recommend trying the software for a month before committing to a longer period.

- Features: While all writing assistants have similar core functionality, they have different user interfaces and feature sets beyond the basics. Choose a piece that meets your specific use-case, without spending more for features that you will not use.

- Platform and Integration: Not all writing assistants are available on every platform, although some are web-based and therefore platform agnostic. Moreover, it is important to decide if you prefer software that integrates into the word processor you typically use, as some are standalone, or browser-extension based.

- Suitability: There is no digital writing assistant purpose-built for expert report writing, therefore, there is a compromise between finding a package with the most useful and fewest irrelevant features, all without materially altering the content of your expert opinion.

While electronic writing assistants are designed for a broad range of professions, this comparison will focus on the feature set most relevant to expert witness reports. Testing was conducted on Microsoft Word where possible, and on a PC with a keyboard, so mobile features were not taken into consideration. Testing was conducted using the most popular individual pricing tier, so enterprise features were also not taken into consideration.

Software

Grammarly

Grammarly is a cloud-based writing assistant, and, founded in 2009, it is both a category creator and the most well-established piece of software in this round-up. Its feature set has evolved from simple spell- and grammar-checking to a full suite of tools including advanced tone analysis.

- Price: Grammarly offers two relevant pricing tiers including a free version, and Premium at $144.00/year or $30.00/month.

- Features: The free version will correct spelling and basic grammar but will only “evaluate” tone. Premium adds tone adjustments and re-writes on a sentence-by-sentence basis, along with a complete suite of advanced structure features.

- Platform: Internet connection required. Available as a browser extension, or a dedicated desktop app that integrates into most PC- or Mac-based word processors. There is also a dedicated web-based editor.

This review is based on the premium tier version, with Word for Windows integration.

Installing Grammarly adds a tab to Word, and automatically identifies potential issues in real-time by underlining words, sentence fragments, or whole sentences. Hovering over the underlined phrase reveals a popup with an explanation and suggestion for improvement, which you can accept or ignore with a click.

Grammarly is tonally aware, and will attempt to determine the degree to which text is formal, neutral, respectful, etc. (A full list is not published, but I have seen at least a dozen tone spectra). After determining tone from context, Grammarly will offer suggestions to nudge a phrase or sentence toward what it perceives to be your intended tone. A window pops up with the heading “check your tone”, followed by “want to sound more formal?” or “want to sound friendlier?” with a list of several suggestions to accomplish that goal. Suggestions are accompanied by emojis which at first, I found off-putting, but grew to appreciate. As texting has become a primary communication mode, emojis have become well-understood markers for tone, and Grammarly has made them a primary piece of their design language. Moreover, emojis serve as a makeshift accessibility feature for colorblind users.

For expert witness reports, maintaining a formal, informative tone is essential, and I found that Grammarly was useful here. While you can let the software determine your tone (which it did accurately), you can also set the tone yourself. After inputting a few expert witness report examples, I found the suggestions useful in maintaining consistency. It suggests re-ordering words, phrasing, and even breaks to enhance pacing. Each report was noticeably improved from the original.

For example, it suggests simplifying:

Original: The design and maintenance history of the Machine do not support the claim of malfunction

New: …support the malfunction claim.

It did so accurately and consistently, clarifying the document without it becoming choppy, disjointed, or unnatural.

On the other hand, I didn’t find the basic grammar- or spell-checking features particularly better than what is baked into Word. It would occasionally suggest a synonym that might be a better option, where Word alone would not, but there were few cases where I felt that there was a significant difference, other than Grammarly’s tendency to offer multiple options rather than just one. If your word processor of choice does not include advanced grammar checking for issues such as subject-verb agreement or more concise phrasing, this may be a more attractive feature.

Like most of the other writing assistants, Grammarly scores your work on a scale for “correctness”, “clarity”, “engagement”, and “delivery”. I find these scales arbitrary, and not particularly helpful, as they are only a measure of whether you have interacted with suggestions for each category. If you ignore an obviously wrong suggestion, your “engagement” grade might never get to 100, so users can potentially waste time worrying over these scales, or worse, accept bad suggestions. I recommend ignoring this feature altogether, in Grammarly and elsewhere.

While Grammarly includes up to 1000 AI prompts per month with the premium tier, I do not recommend using this feature for expert reports, except perhaps to generate a chart or graph with reliable data procured elsewhere.

Suitability: Grammarly’s class-leading tone analysis is a high point, which improved every sample report I fed it, while the basic grammar and spelling tools are only marginal improvements over Word’s own. Expert witnesses who are willing to pay the high monthly price will benefit from the friendly interface, and highly customizable presets. Recommended.

Hemingway Editor

Hemmingway is a more narrowly tailored tool, using a color-based highlighting system to identify writing issues. Suggested changes are paywalled behind monthly subscriptions.

- Price: Hemmingway offers a Free web-based version, or an offline-capable application for a one-time payment of $19.99. AI-based suggestion subscriptions are available at a variety of price points.

- Features: Identifies issues with length, complexity, and word choice. No grammar or spell-check features in the non-AI version.

- Platform: Web-based or offline capable application for PC or Mac. No extension or integration options.

This review is based on the free web-based version, with some premium testing.

Hemingway’s web-based version does not require a login; you can get started simply by navigating to https://hemingwayapp.com/. The interface is an extremely basic editor (think Notepad), where most users will probably paste text from their word processor of choice. While this isn’t overly onerous, especially if you have multiple monitors to move text back and forth, I find it less convenient than assistants which offer direct integration.

The header prominently displays the paywalled features, as most “freemium” software does, including menus titled “Fix Grammar” and “Rewrite”. Two modes, Write and Edit are available. In Write mode, you can type freely into the editor, or paste text. Switching to Edit mode highlights sentences, phrases, and words using a color-based system for a variety of issues, which is where my first problem with Hemingway lies.

Like 5% of the population, I am colorblind. Ironically, there is some evidence that the software’s namesake, Ernest Hemingway, was as well. While color-based highlighting systems are quite popular, Grammarly features accessibility options to tweak colors or add symbols to make the software more usable—neither of which is supported by the Hemingway Editor. Undeterred, I enlisted the help of my non-colorblind partner to differentiate the highlight colors.

After pasting in a few different expert reports, it became clear that Hemingway will highlight practically every sentence, even the most basic ones. For instance, the following sentences were highlighted yellow, for “too long and complex”:

The records show no red flags or missed maintenance steps that might have compromised the Machine’s safety features.

The design and maintenance history of the Machine do not support the claim of malfunction.

Note that I was unable to remedy these (or any yellow highlighted) sentences, no matter how I reworded them. Worse still, are the red-highlighted sentences, which make up about 90% of anything I paste in. Red sentences which are “extremely hard to read” include:

In my experience, malfunctions tend to cause specific and predictable problems, different from what the plaintiff has described.

At this point, I noticed the “readability” stat in the right-hand panel, indicating a grade-level. Expert reports were universally graded at “12” which might be as high as the system goes, but it implores the writer to “aim for 9”. Adjusting the target readability upward is paywalled, so I went ahead and signed up for a free trial, which also includes two weeks of “premium features” such as grammar- and spellcheck.

Now able to see the target readability features, there are only three options available: Accessible (lower grade level), Default, and Technical for “technical and academic writing”. Selecting technical simply changed the red-highlighted sentences to yellow, while the yellow-highlighted sentences. . .mostly remained yellow. There were now a total of 5 un-highlighted sentences across three example expert reports. With access to a limited number of AI suggestions, I decided to see how Hemingway would change a red sentence:

Original: In my experience, malfunctions tend to cause specific and predictable problems, different from what the plaintiff has described.

Suggested: In my experience, malfunctions cause specific and predictable problems. These problems are different from what the plaintiff has described.

Removing words like “tend” can materially alter the meaning of a sentence, which is why double-checking every suggestion is crucial. Moreover, breaking the sentence in two results in a more stilted read. Other highlighted words and phrases were similarly unhelpful, including removal of all adverbs, and shifting passive to active voice.

At this point, it became clear that neither Hemingway Editor, nor the premium subscription are of particular use to expert report writing.

Suitability: At first blush, Hemingway Editor is an attractive free option, but I found the software overly aggressive, highlighting practically everything. The premium product didn’t fare better, with suggestions materially altering meaning, and spell/grammar checking to be basic in scope and function. Not Recommended.

ProWritingAid

ProWritingAid (PWA) is a comprehensive assistant with similar functionality to industry-leader Grammarly, but with an emphasis on style, readability, and avoiding cliches. It was originally intended for creative works, which remains apparent in its current form.

- Price: ProWritingAid offers a subscription plan, including a limited free version, and Premium at $30/month $120/annually or $399/lifetime. Additional pricing options feature more AI queries.

- Features: Comprehensive reports on style, readability, overused words, and cliches.

- Platforms: Internet connection required. Integrates with popular word processors for PC and Mac, Google Docs, Scrivener.

This review is based on the premium tier version, with Word for Windows integration. Note that while there is a free version, it has a tiny 500-word limit.

After running the installer, PWA seamlessly integrates into Word, with a new icon set in the ribbon. Clicking the “Analyze” icon reveals an overwhelming amount of report options, seemingly in no particular order. At least two dozen options are present, ranging from the straightforward “Sentence Length Check” to writer jargon, like “NLP Predicates check”. I ran a full report.

There was a bit of lag as it analyzed my sample expert report of about 20 pages in length, and then highlighted various phrases and words in yet another color-coded system, with no accessibility options. Mousing over the highlighted sentence, segment, or word reveals a popup stating the type of mistake with multiple suggestions, and options to learn about, ignore, or disable the rule in question. I found this extremely convenient, as I could easily ignore instances of say, Oxford comma uses, from within the first underlined instance.

While full reports alerted me to every conceivable failing (the software is comprehensive), thankfully, there are a wide variety of reports which scan for particular issues, including style and tone. The tools are surprisingly intuitive and thorough. For example, I used the “repeats check” tool, which I expected to simply tally instances of the same word or phrase. It did so, but ordered them by length, frequency, and proximity.

One of the issues I’ve had with writing assistants is their proclivity to suggest changes that materially alter the meaning of a phrase. This is fine for creative writing, but for an expert report, it is not. PWA does a better job than some, but it is imperfect, and must be used hands-on. Some of the suggestions included:

Original: in accordance with

Suggested: under

This is typically fine, if a bit informal when referring to a law, however:

Original: at appropriate intervals

Suggested: at intervals

This materially alters the expert’s opinion. The word “appropriate” is doing heavy lifting in the context of maintaining a machine. If an expert simply accepts readability suggestions without considering the ramifications, it could undermine the report, or even the case. Additionally, most legal and technical jargon was detected, and left untouched, which no other program was able to do. Note that most is not all, and it is important to remain vigilant when accepting suggestions. Moreover, it reported common words such as “factor” under “vague or abstract words”. These can be turned off on a word-by-word basis, which is useful, but building a wordlist to ignore is time-consuming.

Like Grammarly, PWA scores your writing on a variety of factors with percentages. I recommend ignoring this feature altogether, accepting only changes that improve the expert report rather than those which increase the score.

Suitability: ProWritingAid is a powerful, comprehensive tool but it feels most suited to creative writing. It has feature and price parity with Grammarly, but many features are irrelevant for expert witnesses, such as comparing your work to famous authors, or auditing for cliches. I found the interface less intuitive compared with Grammarly, although the reports are more granular and comprehensive. Recommended.

Ginger

Ginger is one of the earliest Grammar checkers, even pre-dating Grammarly by several years. While it began as a basic grammar- and spell-check tool (before word processors automatically did either particularly well), it has evolved into a fully featured, yet budget friendly writing assistant.

- Price: Limited free online version, Premium $13.00/month $84.00/annually

- Features: Spelling/Grammar, Correct all mistakes at once, rephrasing

- Platforms: Internet connection required. Browser extension, standalone application for PC and Mac, Word for PC integration

This review is based on the premium tier version, with Word for Windows integration. Note that while there is a free version, it has a limited number of corrections per week among other core feature limitations.

After installation, Ginger integrates into the Word interface, underlining errors in red, and suggestions for improvement in blue. There are no accessibility options to change these colors. Unlike Grammarly, which utilizes pop-up windows, Ginger displays explanations and correction options directly in small bubbles above the underlined text. This can feel a little cluttered at times, especially when dealing with multiple corrections.

Nevertheless, Ginger offers a saving grace: a small floating icon. Clicking this icon brings up a breakdown of all identified issues, categorized and explained. This quick overview (which is similar to Grammarly’s sidebar, but without taking up permanent space) allows the user to identify and address all flagged areas without losing focus on writing.

Ginger offers the ability to make batch changes, and I recommend being extremely careful with this feature. For certain things, like capitalizing a proper noun, it is excellent—a bit like combining Word’s “find and replace” feature with accepting a change. The problem is that when you make a batch change, it is crucial to audit each instance to make sure that the change makes sense, as you can “correct all mistakes” for just about anything Ginger flags.

The software does not correct in real-time, which some writers might prefer, and does not have style or tone-specific tools, which is a drawback for technical, detailed writing. Like other writing assistants, Ginger makes recommendations based on sentence length, word choice, and redundancy, but it does not prompt for (or intuit) the style of writing and suggest accordingly, as do Grammarly and PWA. The suggestions were mostly fine, and my sample expert reports were slightly improved afterwards, but the functionality is basic compared to the competition.

Unlike the other editors in this roundup, Ginger doesn’t offer a score to assess overall writing clarity. Some may find that making changes to hit a number satisfying, but ultimately, I find these scores counterproductive, and appreciate the lack of one here.

Suitability: Ginger provides a solid grammar-checking experience within Word but lacks the style and tone functionality of its more expensive counterparts. Not recommended.

Conclusion

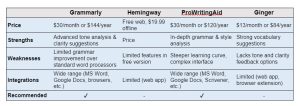

Grammarly and PWA are both up to the task here, with differing approaches and interfaces, but similar results. While I prefer Grammarly’s clean and friendly interface to PWA’s more utilitarian experience, other experts may enjoy PWA’s robust report options, especially if they write outside of expert witness engagements. Tone and clarity are crucial when writing expert reports, according to guests on Discussions at the Round Table, and writing assistant software was able to help with both, improving sample reports when used cautiously and carefully auditing each suggestion. Moreover, frequently flagged mistakes can become a learning experience, improving your writing skills as you edit your reports. While not essential for quality reports, I recommend Grammarly and PWA.

If you are interested in being considered for expert witness work, consider signing up with Round Table Group. For nearly 30 years, we have helped litigators locate, evaluate, and employ the best and most qualified expert witnesses. Contact us at 202-908-4500 for more information or sign up now!