At the Round Table with Business Ethics Expert, Dr. Timothy Fort

May 12, 2023In this episode . . .

Dr. Timothy Fort spoke with us about the importance of training, and the expert-attorney relationship: “I always felt that they had trained me well. They were there to protect me.” There are strategies that attorneys can employ to encourage a successful engagement, including the necessity of being honest and independent. Dr. Fort remarked on the topic, “As a potential expert witness [I] really want to hear the words from the lawyers that that [they] want your independent opinion.” Additionally, we covered ethics for experts, maintaining an agreeable composure during cross, and report writing.

Episode Transcript:

Note: Transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

Host: Noah Bolmer, Round Table Group

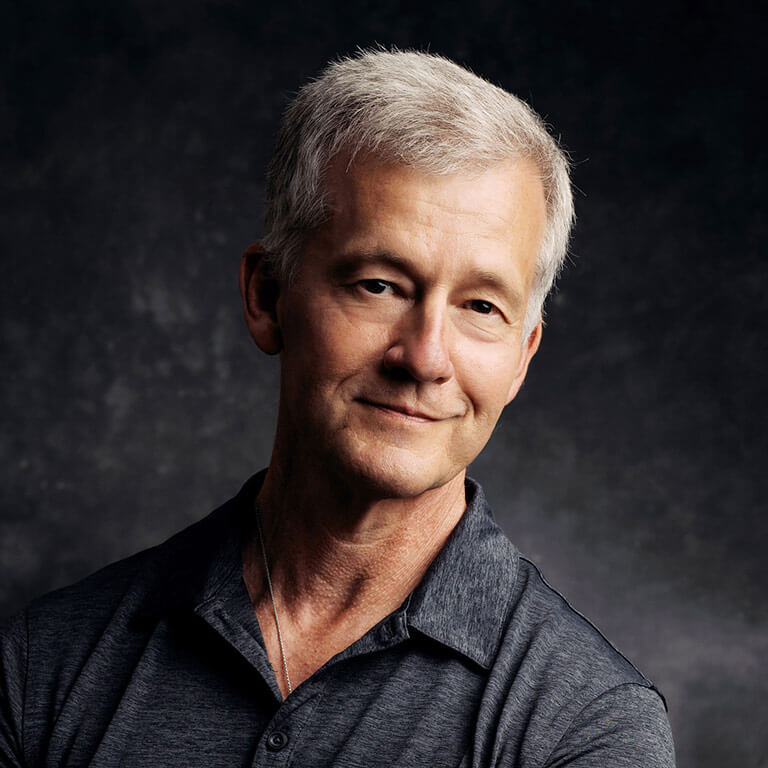

Guest: Dr. Timothy Fort, Eveleigh Professor of Business Ethics; Kelley School of Business, Indiana University

Noah Bolmer: Welcome to Discussions at the Round Table. I am your host, Noah Bolmer. I am very excited to speak with Dr. Timothy Fort, he is the Everly Professor of Business Ethics at the Kelley School of Business at Indiana University. He coordinates the undergraduate ethics program at Kelley, where he received the Distinguished Career Faculty Award. Dr. Fort has taught Business Law and Business Ethics for nearly four decades and is an esteemed author with several published books and articles. He holds a Juris Doctor (J.D.) and a Ph.D. in Theology and Business.

Dr. Timothy Fort: Thanks very much for having me. I look forward to it.

Noah Bolmer: Let’s get into it. You have made a career of teaching and writing on various topics, but chiefly on the multiple intersections of ethics, public policy, and social issues. Tell me a little about your background and how ethics became your primary area of inquiry.

Dr. Timothy Fort: It started when I was in my first year of law school at Northwestern, and I was disillusioned. We learned all these incredible advocacy skills, but I did not think we had paid enough attention to ethics. I got lined up with an Associate Dean who said, “Well, the law is value neutral.” I thought then and now were ridiculous. I knew I would go back to practice law with my father in my hometown of 800 people. I did not have to spend summers doing summer internships, so I got a master’s degree in ethics during summer programs at Notre Dame, my undergrad alma mater. That led to an ongoing interest in ethics throughout my career, and I got a break after teaching business law. Loyola University said their priest had decided to take the summers off, and did I think I could put together a business ethics class? I did, and I loved it. It kept going from there.

Noah Bolmer: That is an interesting story. It has been your primary focus since the very beginning.

Dr. Timothy Fort: It has always been a focus of mine and has continued throughout my entire career. Once I expressed an interest in ethics, unexpected avenues opened for me. It was a perfect thing for me to pursue. I would say one other thing regarding your introduction and coordinating the Kelly ethics program; we have the largest ethics faculty in the world. We have 22 full-time ethics faculty, and I am sure that is the biggest in the world. It is remarkable. I wish I could say I had some great strategy I designed years ago, but frankly, it was dumb luck and some good opportunity.

Noah Bolmer: Absolutely. Unfortunately, more universities do not have such robust ethics programs because it is a key area. I am a former attorney, and I agree with you. I went to law school at Case Western in Cleveland and had a similar experience where many professors were ethics neutral. It is a neutral topic that I wish people were delving into more. It is impressive that you have built an entire career out of this critical area. How did you parlay this into expert work?

Dr. Timothy Fort: Sure. Dumb luck. That is the story of my career.

Noah Bolmer: That is the through line here.

Dr. Timothy Fort: I was asked to do ethics testimony work for a while and just turned it all down. At the time, I was going through my promotions from assistant to associate to the full and felt I needed to focus on my academic career. Nine years ago, I got one that struck me as an interesting case. It was to assess the Ethics and Government Act as it applied to an individual that was part of what was then, and I think still is, the largest tort case in American legal history, a $5.7 billion court case. I saw that my kids were getting ready to go to college. I knew the law firm had high respect for the law firm in Chicago and I thought, “This is a pretty interesting case, and it is a big case. Let’s give this a try.” It was fantastic.

Noah Bolmer: Even so, in your first go around as an expert, it was a fantastic experience. I do not always hear that. Did they reach out to you?

Dr. Timothy Fort: Someone in their office was in one of my classes or knew someone who had me in class. They reached out to me because they needed a rebuttal witness. They called me, and we hit it off right away. It was Winston and Strawn in Chicago. They were fantastic and assigned two lawyers to coach and train me to do mock interrogations. They could not have supplied a better orientation for how to do this. I was deposed, and they settled the trial, so I did not testify. I went through a rigorous deposition, and they were there for me. I always felt that they had trained me well. They were there to protect me and cheer for me. It was a feeling that they were all in for Tim. It was not that they were doing advocacy for their client, which they were doing, but they were personally supportive of me as well. It was a high-stakes case and a big-time firm from Washington, D.C., was on the other side. It was throwing me into the deep end, but it worked out well.

Noah Bolmer: Let’s get a little bit more into that preparation that helped you so much. What specifically helped you as an expert? What specific preparation methods, coaching or mock depositions? What specially were those things that you would say attorneys should be doing to help the experts they are bringing on?

Dr. Timothy Fort: As a potential expert witness, I want to hear [from attorneys], “We want your independent opinion. We would like you to be supportive of our case, but if you do not think we have a good chance, we would rather have known now rather than later.” I believe that it is essential for an expert witness that you can express your beliefs and not get yourself into a trap of “that is not what we want you to say” and “this is what you want to say.” That is important to me. Another thing is a promise that whatever you believe you need to render that opinion about the number of depositions, or if you need to interview somebody, you let us know. Those are two critical things that have happened in all my cases. They create an avalanche of work for you to go through. In my case, I am not a scientific medical expert, so I do not know, but I am guessing that they probably do not read as many things as a law and ethics person is reading. They may be doing more scientific analysis, testing, or something like that, but I am reading a thousand to maybe even two thousand pages for a case. As I am going on, I need to check in with the lawyers. Sometimes they can help me fill in the blanks, and I can push them on questions I do not understand. Having regular check-ins helps make sure I am not off on the wrong track or misinterpreting something.

A third thing I want is, when I am interviewed, I want them to promise that they will grill the heck out of me before we go into the deposition. I have referred to that first deposition when we did two days of the evil counselor. Then I will fill in the blank of the counselor’s name because she was ripping me to shreds, and it was what I needed because she made me more focused. Even if I knew the answer I wanted to give, there was a stylized way of giving it. I mean, it is not just a conversation, and so, getting used to how to speak was important. Assuring the expert that they want an independent opinion, giving you everything you want, helping with occasional check-ins, and providing an attorney to rigorously engage with me.

Noah Bolmer: How difficult is it when they are grilling you? How do you deal with stress and pressure? Is it because you have been well prepared for it, or do you have other strategies or tactics to bring it down and ensure everybody keeps calm and things are objective?

Dr. Timothy Fort: The hardest one is the preparation. I participated in athletics as a kid, and our coaches always said that the practice had to be more challenging than the game. I believe that. I want to do well for attorneys with whom I have developed a relationship, but once you get into the game, it is essential to remember that it is a bit of a game. It is stylized and rarely personally about you. Even when people are pressing on you, it is something that they must do. They are not necessarily tearing you down as a human being but pressing on your views. As an academic, I have trained with that because it happens when you present a conference paper. People are picking at you. If you can keep it that way, the stress level decreases.

There is an adage that a person’s biggest strength is probably their weakness too. That is true of me. In my first deposition, my attorneys that counseled me said, “Now be careful of these guys on the other side because they will be friendly before they go to trial. They are going to chat you up, but then they are going to go in hard. You must remember that you are still in the midst of this fight, and it is not just a friendly conversation. I laughed and said, “Oh, I play that game well because I played many sports. Baseball was my favorite, and I stole a lot of bases. I was pro in chatting up the first baseman when I was on first base. We talked about all kinds of things. A party we went to last week, a pretty girl in the stands, or whatever, but I knew when I was making my break to steal second base too. So, I said, “I can. I can handle that.” It is a type of game. You are there for what you are supposed to do.

Noah Bolmer: Right.

Dr. Timothy Fort: You are defusing a little tension in the last deposition that I did. I cannot reveal details of it, but there was one point where I truly admired and liked both companies. I thought that the party I was speaking on behalf of was correct and the other side was wrong with the particular thing they were doing, but I liked their work. The opposing counsel said, “Do you have any personal relationships or views on the company? And I said, “I like both companies.” They said, “Do you like your company?” I said, “I just said, I like both companies.” He said, “I know, but I have to ask the question.” I recognized that he had to ask that question even though he knew the answer. He has to make the record show that he asked, “Is there a personal bias you have?” That was my strength because it helped me defuse situations. I have a bifurcated way of getting into that weakness. As you probably can tell, I am an affable guy, and my counsel has frequently warned me, “Tim, this is not a conversation. I mean, this is a fight, so answer the question. Just answer the question. You do not have to go beyond the question. Just answer the question. I know you want to be affable, but do not jump into your answer. Wait a second, collect your thoughts, and then understand the words answer the question rather than jump into it and spin-off on a bunch of tangents because you are this friendly professor who likes to talk.” I must remember that affability and recognizing that you are in a game situation reduces stress. So, it is a little of both.

Noah Bolmer: You might say that it is a little more like chess than boxing to some degree

Dr. Timothy Fort: Sounds like a good analogy to me, but sometimes I see boxers that give each other a hug or something like that afterward. I have not done any boxing except when I was about 9 years old and in the backyard with some friends. It is a good analogy.

Noah Bolmer: Do you find ethical considerations when being an expert? You were talking about how you like both companies but are employed by one and not the other. What are the ethical considerations in performing as a witness and telling the truth? As you said, you will be honest about your expert opinion. What ethical considerations are important to that?

Dr. Timothy Fort: That is a great question, and why I want to hear assurances that they want to have my independent view at that first meeting. Then I can speak authentically and truthfully about what I believe instead of being a paid advocate. I may disagree and struggle with that when practicing law. There were a couple of occasions when I thought my client was degenerate. Representing them in the courtroom as an expert was hard for me, as an expert, I want to speak truthfully about what I believe. I have said to my counsel, I can say these things are all true, but I think this is weak. At this point, that got a bracket off the table. They were aware of that and appreciated it. The most significant ethical thing for you is honestly saying what you believe. You can frame things in words that are perhaps more helpful to your side than the other. But without going to the point where you are not misrepresenting what you authentically believe in, at least for me, is essential.

Noah Bolmer: One of the other things I found interesting while reading your biography was the concept of cultural artifacts. It is a new area of inquiry into how we can relate to one another in more hostile situations. That applies to our conversation about being an expert, dealing with aggressive counsel, or whatever the case is. Tell me a little about your cultural artifacts approach to solving the differences between people.

Dr. Timothy Fort: That is a difficult question because you can get me talking about this for about five years. It is the heart of where I am right now.

Noah Bolmer: I have as much time as you do.

Dr. Timothy Fort: Let me back up for just a second. My brand has always been I get credit for inventing a sub-academic field of how ethical business behavior reduces the amount of violence in the world. We talk about the ethical business culture that maps well with anthropologists. Say our attributes are relatively non-violent societies. I started to write about that in about 1999. There is a vast subfield that developed due to my, and others, who were the only people that were writing. In fact, many of my friends said, ” Please do not do this because you are committing political or career suicide.” It is weird, but I have written four books on that topic and won two Best Book Awards. That is what my brand is. Then I came out here to Indiana University. I was previously at George Washington University, right in the middle of Foggy Bottom, the White House, the State Department, and the US Institute of Peace. One of the great things about Indiana University is it has arguably the world’s best School of Music. I have a music background, and my kids took piano lessons when they were six and nine years old. It struck me as I was waiting outside of their room. Why couldn’t you use music to nudge people toward thinking about things in a certain way instead of other ways?

We do not just listen to music. We tap our hands and feet, bounce our heads, sway, and dance. That turned me on the notion that we could use cultural artifacts, music, sports stories, films, suppers, and our pets to nudge us into thinking and looking at things in a certain way. We look at things in a friendly manner instead of a combative way. You mentioned boxing earlier. If I want to think I do this as an exercise for my students or if I want to put myself into a combative state of mind, I will listen to the theme from Rocky. But if I want to put myself in a state of mind where it is the golden rule and you are reaching out to others and being friends, I will listen to the theme from Friends. Listening to music puts you in a different state of mind. So, those are the nudges that become bridges because we can find common ground, even if we disagree politically. socially or in a deposition. That gives us common ground beyond that thing in which we are conflicting. It is a familiar story about a sporting event, a piece of favorite music, a favorite movie, or telling stories about our pets. There is an organization called Braver Angels in this country that gets conservatives, liberals, Republicans, and Democrats to talk with each other.

How do you start that conversation? That is a tough conversation to start. One of the things that Wall Street Journalist and Indiana University graduate Elizabeth Bernstein told me in an interview is that they often start talking about their pets. It is like, how is the weather? It is an icebreaker. I translate all that and am writing like crazy on that. I have got two books going and maybe a third. In this last deposition, I did a little homework in advance, and I saw that the opposing attorney that was going to be deposing me was from the University of Michigan, where I spent the first eleven years of my tenure track career.

I introduced myself when we came in, shook hands, and said, “You are a Michigan man.” Then, it quickly came out that both of our sons played baseball. So, we were telling baseball stories. That goes to what I was talking about earlier. That is finding a way to connect with somebody, but you are still in the competition. I think those small things defuse the atmosphere a little. I do not want to go too far. Again, people are here for a reason, because the legal system is an alternative to violence. That is why we praise it. How do you settle disputes if you do not have a legal or arbitration system and you resort to fighting? I think it can create an atmosphere that is a little more professional and not quite as harsh as it might be otherwise. I do believe that cultural artifacts can have a role in an expert witness situation.

Noah Bolmer: How do you walk that line between wanting to have those connections, being affable, and remembering it is ultimately a combative situation? I know we discussed it before, but what is that line? Is it fuzzy, or is it a hard line?

Dr. Timothy Fort: It is a fuzzy, wobbly one, for sure. It is because of the reasons I indicated earlier. I do not have difficulty, just like when stealing second base. I have difficulty once the questioning starts. I will not break in and talk about baseball or anything like that. I mean that it is not difficult to separate. What is difficult to separate once you are chatting, being interrogated, and have been chatting to hear the question and move into conversational mode instead of interrogation mode. I struggle with that, and one criticism my counsel has given me during breaks is slow down. “Tim. I want you to take a deep breath before you answer the question because you are being too friendly. It is not a conversation, they said. It is not bad, but you said most of your work is terrific. But you will be better if you take that deep breath and then stay within the lines that you have established.” I stay within the lines, but you can seep into my mind. Maybe not everybody in my mind. I can fall back into the kind of friendly chat I had with a guy outside being under oath.

Noah Bolmer: It looks like you have been an expert witness a couple of times.

Dr. Timothy Fort: I have been deposed three times and am currently under retainer for a fourth one. I have served as an expert witness in a written document or written opinion. On three other occasions or instances, those were separate from any internal memo to attorneys, as opposed to something you will have to testify on behalf of.

Noah Bolmer: What are those documents like? How do you prepare for that?

Dr. Timothy Fort: Those are fun. Those are almost like an academic exercise. In fact, two wo fo them were for the same set of attorneys for which I did my first deposition. They wanted an internal memo for something else. One of them turned into a law review article. A question that came up in the case was not directly related to my case. We all agreed it was an interesting question, and if I were on a stand, It was more of a business law ethics than the particular thing I was testifying about. It would probably be good for you to have a good foundation if someone interrogated you. Have you thought about the ethical implications of blah blah blah? I was like, we should analyze that to protect me and ensure I have an answer, and I am not fumbling around if that ever happened. It is like an internal memo a third-year law associate would do in a big firm or a draft of academic articles. We would agree on the assignment, and then I would write the draft. There was not as much back and forth on that because it was not something they were prepping me for specifically. Then I would give them a draft, and they would give me a response on that, and then I would refine it. It was ready to go. It was another arrow in our quiver in case we needed to use it. Those were a lot of fun because you have no pressure.

Noah Bolmer: Right.

Dr. Timothy Fort: Well, you do not have any pressure. We did it to protect me if it did come up, but we knew it was proactive instead of something you would get grilled on.

Noah Bolmer: Do you find that there is any difference depending on forum? In other words, do you have to know the ethical framework where you are, then federally. and maybe internationally, I do not know if you have done any international expert work. Have you had any calls to do significant research to determine the governing laws?

Dr. Timothy Fort: It is a great question. I have not done international work. In the second case that I did, it was a fiduciary claim case of a non-compete clause. An officer moves to another company, and a dispute arose, and over that multiple states were involved. The key state of business and the state of incorporation. States differ, particularly on the fiduciary duty and covenants not to compete—the key state of business, the state of incorporation, etc.

Noah Bolmer: Right

Dr. Timothy Fort: I had to do state-to-state research to know what laws applied to our discussion. The other thing related to your question has been interesting for me as a law slash ethicist. In the first case, the opinion that they asked me for was specifically the legal interpretation of the Ethics and Government Act. That is a specific law pertaining to governmental employees. I have that legal analysis, but then I added some more pure ethics analysis. The legal part was relevant, and they did not care about the other part. it. The fiduciary duty case was federal, and the judge said, “I’m the one who decides what the law is. Thank you very much. An expert is not going to tell me what it is.” But they were interested in the ethics part of it. They did not want the legal part of it, and they did not want the ethical aspect of it. Now, when I go into a case, I ask what you want to know from the lawyer. What is the jurisdiction? What do they want from me? Do they want legal? Do they want ethics? How do we combine both and structure it to do both? That becomes an interesting question, particularly for my work. How do you blend those or try to get the maximum opinion? How can you fund me without violating any jurisdictional preferences you have in place?

Noah Bolmer: One of the other attorneys said, “I am sorry. For that reason, one of the other experts I was speaking with recommended having LexisNexis or Westlaw accounts. Do you keep a Westlaw or LexisNexis account to easily search the case law or the relevant documents in any form?”

Dr. Timothy Fort: We have that available through our university, and I do use that. Since I have a record of being able to turn expert witness cases into actual research publications, they are okay with me utilizing it for that purpose. They see that as an opportunity even though I use it for something outside the university. At the same time, I use it in my classes all the time. For the experiences and things that I write about. It is helpful to have, particularly if you are studying a case. I can find many things on the Internet these days, but it is beneficial to have something like that if you have to figure out what Mississippi says instead of what Michigan says.

Noah Bolmer: Do you have any other tips or strategies you would like to share with other experts or potential experts going forward?

Dr. Timothy Fort: I know people get stressed at this, and I used to get stressed about it, but the first attorney that had my work was excellent. I got ready for the second one and developed a relationship with these people. They became your colleagues, and I said, “That first one was just so good, but I am still a little stressed about what the next one will be like.” Tim, so you have a bad one. That means that you had one good one and a bad one. You are batting .500, and that is not bad. If you have a bad one, remember that you had one that ended up being good too.” That is another one of those things that release stress. Most of my experience, at least to date, might change, but in those three, I had good attorneys and respectful questioners. They did their job. They were challenging and rigorous, but they were not jerks either. Now you can have a jerk. I am not saying that they are not out there, but it is not as personally risky as you might think it might be.

Noah Bolmer: Tim, thank you. I appreciate you being on the show and look forward to speaking with you again. It was a fascinating conversation.

Dr. Timothy Fort: Thanks for having me. This was fun.

Subscribe to Engaging Experts Podcast

Share This Episode

Go behind the scenes with influential attorneys as we go deep on various topics related to effectively using expert witnesses.

Dr. Timothy Fort, Eveleigh Professor of Business Ethics; Kelley School of Business, Indiana University

Dr. Timothy Fort is the Eveleigh Chair in Business Ethics at the Kelley School of Business at Indiana University, where he coordinates the Undergraduate Ethics Program—the world’s largest ethics program. He is the recipient of the 2022 Distinguished Career Faculty Award from the Academy of Legal Studies. Dr. Fort is an accomplished researcher and author, with over fifteen published books, over twenty academic works, and dozens of research awards.

Find more episodes:

Expert Witness & Attorney Relationship, Expert Witness Report Writing, Expert Witness TestifyingBusiness ethics are defined by the standard of behavior that an organization establishes in the workplace. Many businesses have a difficult time properly defining what should be viewed as “acceptable or unacceptable”. Our business ethics experts have honed their expertise through their work as consultants, ethics scholars, and corporate executives.

Laws are important for society because they serve as rules of conduct for citizens. They provide society with guidelines of what conduct is acceptable. Without laws, conflicts between social groups and communities would be common occurrences.