Witness Preparation and Jury Persuasion

Copyright 2020

Daniel A. Kent, Kent & Risley LLC

David A. Reed, Kilpatrick Townsend & Stockton LLP

Dan Rubin, J.D., Round Table Group

Round Table Group’s National Business Development Manager, Dan Rubin, was a presenter at the Atlanta Bar’s 16th Annual Intellectual Property SpringPosium on May 26, 2020, along with Daniel A. Kent of Kent & Risley and David A. Reed of Kilpatrick Townsend & Stockton. They presented on Expert Witness Preparation and Jury Persuasion.

Introduction

Witness preparation and jury persuasion go hand in hand. The story of the case is told to the jury through witnesses, who are also the conduit for introducing documents and exhibits to the jury. An attorney cannot effectively prepare a witness to testify at trial or even a deposition without first understanding how the witness’s testimony fits into the overall plan for persuading a jury to find in the client’s favor. Similarly, the plan for persuading a jury should consider the witnesses through which the story of the case will be told, including both fact and expert witnesses. Like pieces of a puzzle, the witnesses and story must fit together to form an understandable and compelling presentation.

What is Persuasive to a Jury?

Understand Jurors’ Situation

Before jury selection begins, most jurors would rather be somewhere else doing almost anything other than serving on a jury. However, by the time the venire views the typical video on jury service, is brought to the courtroom, sworn-in by the judge, asked questions in voir dire, and selected for the jury, most jurors have bought into the process and are ready, willing, and able to do their civic duty as best they can. Much like we have all experienced during the disruption of the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic, attorneys should understand, that jurors at this stage are still trying to figure out how the logistics of serving on a jury will work given their employment, family, and other responsibilities. They know little about the case or the attorneys but are quickly learning from observation how courtroom protocols function and the role of the judge. Everything about their experience is new (except for those few jurors who have served before or the rare lawyer picked to service on a jury).

Looking for which side to trust

Jurors selected for service generally take their role very seriously and want to do a good job. They have observed and understand that the trial judge is in charge, and that both sides defer to him or her in open court. The courtroom is designed to impress upon everyone the authority of the judge and the solemnity of the proceedings within it, and that intent is not lost on the jurors.

Otherwise, though, selected jurors generally have no preconceived notions about the parties, the lawyers, or the case (otherwise they would have been stricken). They are essentially a blank slate. While they may not have any knowledge about the factual disputes at issue in a particular case, juries are very perceptive and are very good at weighing credibility.

From the moment they first enter the courtroom, jurors are looking for someone to trust, other than the judge whom they reflexively trust. The side who appears more worthy of trust to the jury is often the side the jury will believe when it comes to disputed facts. This question of trustworthiness has many facets, including how your side carries itself, and interacts with the judge, courtroom personnel, opposing counsel, and each other.

Story/Theme that Makes Sense and Explains the Testimony and Documents to be Presented

One of the many factors that inform a jury’s determination of which side to trust is whether the story or theme of the case makes sense, hangs together, and reasonably explains the evidence the jury is going to see and hear. The jury starts evaluating this factor from the first time they hear anything about the case – which is typically opening statements but can sometimes creep into voir dire.

The importance of a sensible story and theme cannot be overemphasized. As a result, identifying a sensible story and theme should not be left to the last minute before trial. A working theory of the story and theme should be part of the initial intake and case workup, whether you are representing the plaintiff or defense. While this story/theme may evolve as the case progresses and additional facts are learned, it is remarkable how often initial stories/themes formed at the beginning of an engagement end up being the stories/themes that are tried. One explanation may be that the initial impressions formed by counsel most closely resemble how a jury will hear the case – fresh, and for the first time.

Starts at Beginning of the Engagement

What is the Story/Theme of the Case?

A good case story/theme should be memorable, should explain the facts in a way a non-legal and non-technical person can understand, and should lead the jury to the conclusion you want them to reach. Counsel should also not underestimate a jury and its ability to grasp the complexities of a given dispute. Juries are capable of synthesizing a large amount of information and assembling it into a coherent narrative to reach a fair result. A story/theme must explain the facts – even the bad ones – and why the case is important enough for the jurors to upend their lives to help resolve this dispute. In formulating a compelling theme, below are some basic starter questions attorneys should ask and understand as they begin to formulate a story/theme:

Patent

a) What was the invention (problem/solution) and its importance?

b) What did accused infringer do?

c) What damages did the alleged infringement cause?

d) What defenses exist?

2. Trademark

a) What is the mark and its value?

b) What did the accused infringer do?

c) What damages did the alleged infringement cause?

d) What defenses exist?

Copyright

a) What is the work and its value?

b) What did the accused infringer do?

c) What damages did the alleged infringement cause?

d) What defenses exist?

Trade Secret

a) What are the trade secrets?

b) What is/was the misappropriation (what happened)?

c) What damages did the alleged infringement cause?

d) What defenses exist?

Beyond these basics, counsel should consider the case’s weak points and how those should be addressed. For example, in a patent case if certain prior art may pose a problem to a patent owner, what are the key differences between the asserted claim(s) and the art? If apportionment is an issue for damages, what is the relative value of the asserted invention as compared to the accused product as a whole?

By asking these questions early, counsel can begin to formulate a working story/theme that can be used in conducting discovery, preparing witnesses for deposition, and ultimately for trial.

Through Which Witnesses Can that Story be Told?

A jury trial presentation consists of three primary parts: opening statement, witness presentations, and closing argument. The most amount of time before the jury will be spent on witness presentations, so it is critical to start thinking about potential witnesses from the very beginning of a case in parallel with developing your story/theme.

For fact witnesses, consider the inventor and/or key technical personnel in a patent case, sales/marketing professionals in a trademark case, and the CEO or other high-ranking person to serve as the face of the party to the jury. Also consider who the key fact witnesses are, and how they will present to the jury. Consider any available alternatives if you identify a witness that may be problematic in front of a jury.

The importance of experts is difficult to overstate. Expert witnesses in IP cases often dominate trial presentations, both in terms of time and importance. As a result, the ability of such witnesses to communicate clearly to non-technical and non-financial folks about complex topics is the most important skill to find. Experts should be vetted as early as budget will allow in a case. Since experts often make or break IP cases, and since such experts often face Daubert challenges to being allowed even to testify, extra care is required. Take the time needed to interview multiple candidates, and be sure to focus not only on their resumes and technical abilities, but also how clearly they communicate complex issues.

Discovery/Investigation

The purpose of discovery and investigating a case is to develop facts, documents, and witnesses to support (or revise, if necessary) the story/theme of the case. While it is important to be flexible as new information is learned and to cast a reasonably wide net during discovery, having a working story/theme will help focus your efforts on useful information and test/revise the story/theme as needed.

When conducting discovery, counsel must necessarily follow the evidence where it leads, but also should have an endpoint in mind – the story/theme that ultimately will be presented to the jury. For example, when conducting depositions, counsel should be thinking about getting the admissions that will be needed to effectively cross-examine the witnesses at trial in order to tell its side of the case. Discovery is not conducted for its own sake but instead is a means to an end – an effective trial presentation.

Witness Preparation

Witness preparation may be one of the most under-appreciated skills and tasks a trial lawyer does. It takes time, and lots of it. It requires anticipating factual and legal issues concerning the anticipated testimony, and providing a framework for witnesses to deal with unanticipated issues.

For depositions of fact (percipient) witnesses and inexperienced expert witnesses, preparation also requires teaching an unfamiliar set of skills to folks who don’t typically appreciate the difference between a conversation and testimony. For these witnesses, be sure to set aside the substantial time needed to review these matters with the witness, role play with mock question and answer sessions, review documents (where appropriate), and explain the process and how the witness’s testimony fits into the overall case story/theme. This is also a good opportunity to test or refine your working story/theme.

Witnesses should not be expected to remember everything you review during a deposition preparation session. Instead, the witness should leave the session with a clear understanding that they should, first and foremost, tell the truth. They should also leave the session with a simple, memorable strategy for approaching the deposition.

Counsel should also note any legal issues that are likely to arise during the deposition and do the legal research beforehand so there are no surprises. You don’t want a lack of preparation to suggest to the witness they aren’t in good hands. A witness who loses confidence in his or her counsel is more likely to forget the preparation work done, grow nervous during the experience, and say something regrettable during testimony.

Trial testimony is similar to deposition testimony, but with the added feature of being presented in live, in open court, to an audience that includes the jury, the judge, both sets of counsel, courtroom personnel, and the gallery. It can be a very intimidating setting. The witness should understand that the jury is the primary audience, and should talk to the jury. If the court will allow it, try to stand behind the jury so the witness is looking toward the jury when he/she is looking at you. Prepare the witness to look at the jury when answering and talk to the jury as much as possible.

In addition, while deposition testimony can often be seen as playing defense, trial testimony typically involves both offense and defense: telling your own story, then defending it on cross-examination. Trial testimony preparation begins with a thorough review of any deposition transcript given by the witness, as well as reviewing key documents likely to be introduced at trial, and any specific issues the witness is likely to face. Fitting the testimony into the story/them of the case is especially critical when it comes to a persuasive trial presentation. And counsel should always work with witnesses to plan testimony that will be logical, coherent, interesting, and compelling.

For experts, some have testified in court multiple times, while others have not. In either case, the expert should understand his audience is the jury. While likely not technically trained, the jury is intelligent and should be treated with respect. Much like students in a classroom, juries want to be taught and to learn so they can have the information needed to do their job. Teach. Explain. Illustrate. Trust that if the expert does his job well and testifies consistent with the story/theme you are presenting, the jury is capable of understanding even the most technical presentation. The expert’s approach should be to help and inform the court and the jury, and to defend his or her opinions in the interest of helping lead the Court and the jury to the truth.

Challenges to Experts

Currently, challenges to expert witness testimony seem to be commonplace. While some statistics may suggest that such challenges may not be as frequent as it seems, good practice is to anticipate potential challenges to expert testimony as early as possible, and to plan for avoiding them beginning with the expert’s report and through the expert’s deposition. An expert cannot be persuasive to a jury if the jury never gets a chance to see or hear the expert testify.

Nonetheless, recent statistical trends may be enlightening and attached are some recent statistics compiled by Round Table Group for consideration.

Round Table Group Presentation

Round Table Group has been connecting IP attorneys across the country with science, technical, and financial/damages experts for their intellectual property litigation for over 25 years. Through our affiliation with Thomson Reuters/Westlaw over the years, we have had access to a treasure trove of data on litigation trends. I am going to share some of the high-level findings with respect to trends in Daubert challenges in intellectual property litigation, then drill down in detail into specific trends in patent litigation specifically, and the reasons for and results of those challenges.

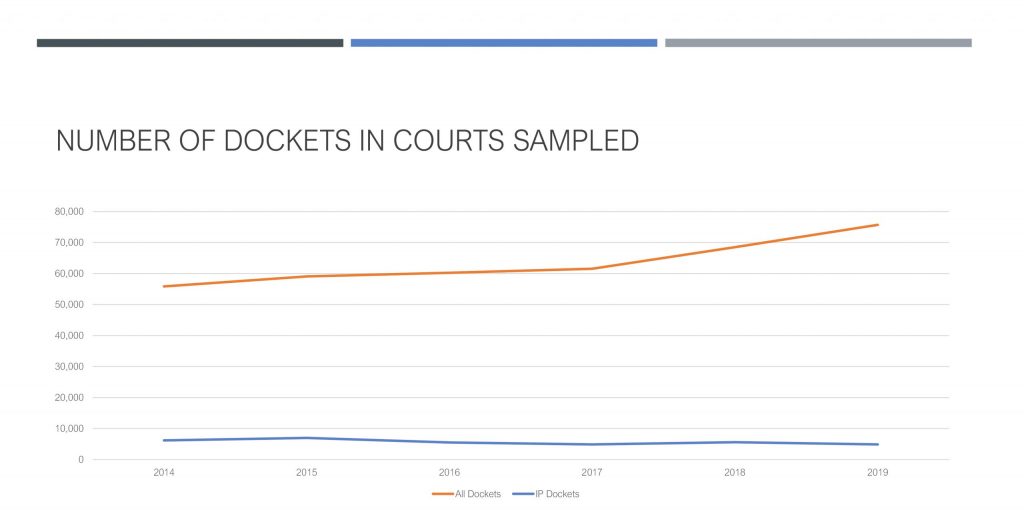

- First, a few notes on the data. We looked at Daubert challenge data in IP cases from six IP litigation-heavy courts, from 2014 to 2019:

- United States District Court, D. Delaware

- United States District Court, E.D. Texas

- United States District Court, N.D. California

- United States District Court, D. New Jersey

- United States District Court, C.D. California

- United States District Court, N.D. Illinois

- All data is derived from Westlaw Edge’s Litigation Analytics.

- The data is a subset of court documents. Westlaw extracts its sample size from a randomly pulled sample each year.

The number of dockets in all matters from courts sampled was close to 60,000 from 2014 to 2017. In 2018, that number increased to close to 70,000, and in 2019 to about 75,000. The number of dockets in IP matters from courts sampled ranged from 6,000 to 8,000 from year to year.

The number of dockets in all matters from courts sampled was close to 60,000 from 2014 to 2017. In 2018, that number increased to close to 70,000, and in 2019 to about 75,000. The number of dockets in IP matters from courts sampled ranged from 6,000 to 8,000 from year to year.

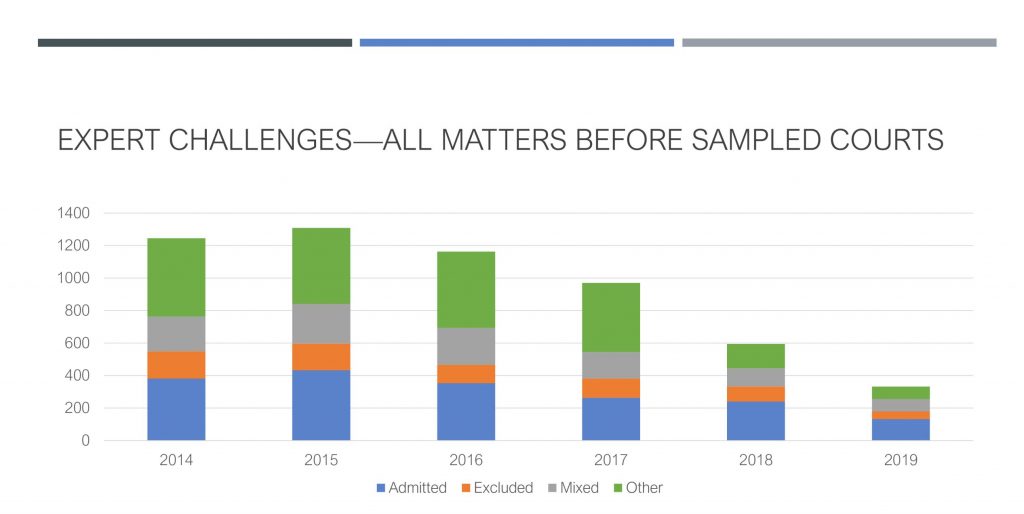

Starting with challenges in the sample courts in all practice areas, to expert testimony of all types: after an increase from 2014 to 2015, challenges overall decreased steadily each year thereafter, from 2015 to 2019. The trends in the results of these challenges—admitted, excluded, mixed*, and other**—tracked this decrease proportionally.

*mixed = admitted in part and excluded in part

**other includes denied as moot, withdrawn, and undetermined outcomes

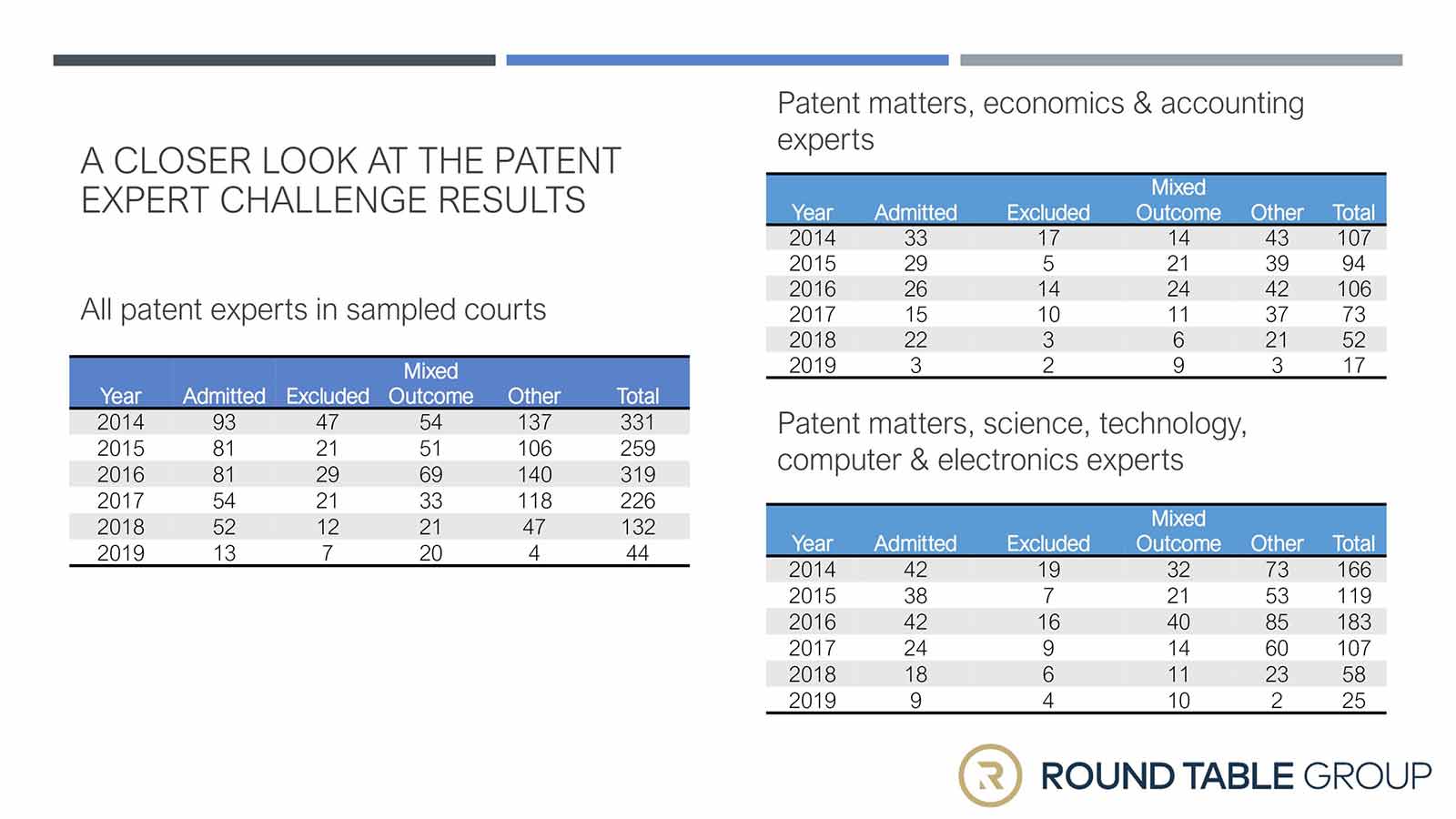

Looking at patent cases specifically, and challenges to scientific, technical and financial/damages experts combined, after a decrease in challenges to these financial and non-financial experts from 2014 to 2015, and then an increase in 2016, there has been a steady decrease since 2016. The number of instances of expert testimony excluded declined each year, as well as the number of “mixed” and “other” outcomes, with a precipitous decline from 2018 to 2019. While the instances of expert testimony admitted stayed relatively the same between 2014 and 2016, and 2017 and 2018, they also precipitously declined from 2018 to 2019.

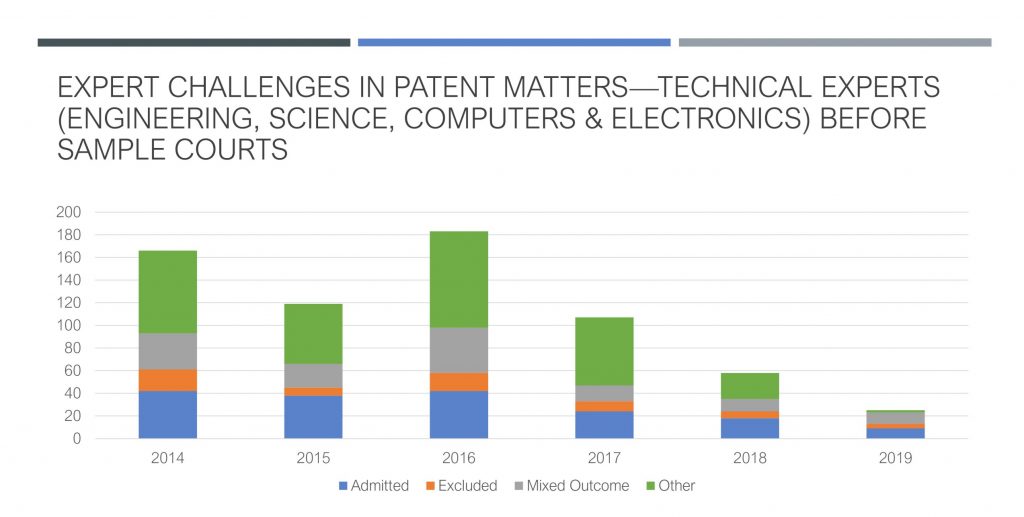

Looking at challenges to technical experts only (engineers, biotech, computer/electronics experts, and other non-financial technical industry experts), the trends are similar, both overall and with respect to the instances of expert testimony being admitted and excluded.

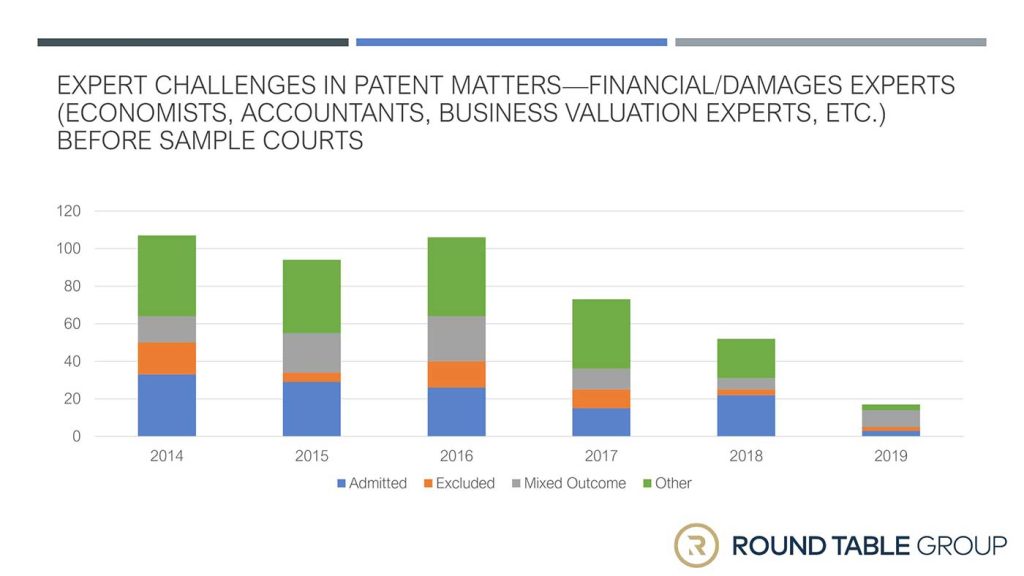

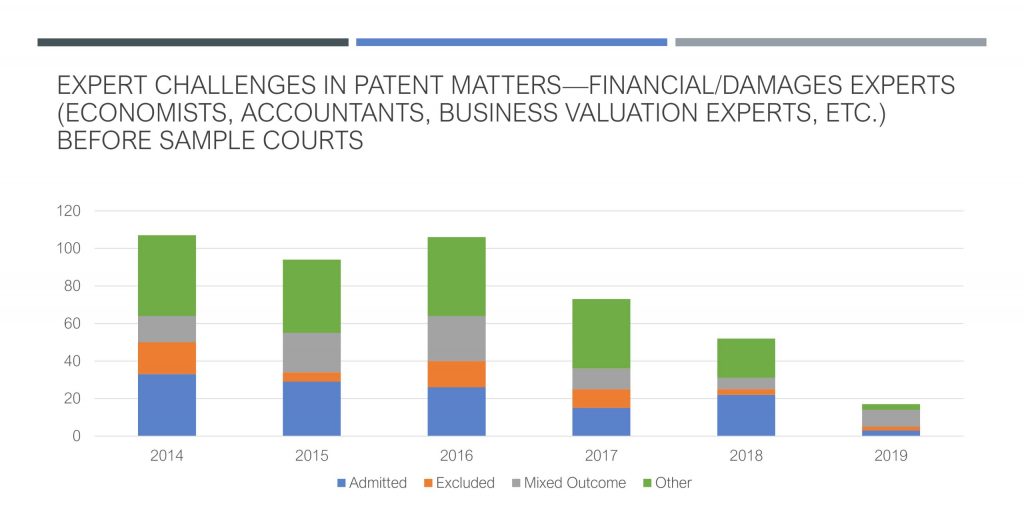

Looking at financial/damages experts only (accountants, economists, appraisers, statisticians, financial analysts, etc.), the trends were very similar, with a bit less of a change between 2014 and 2016.

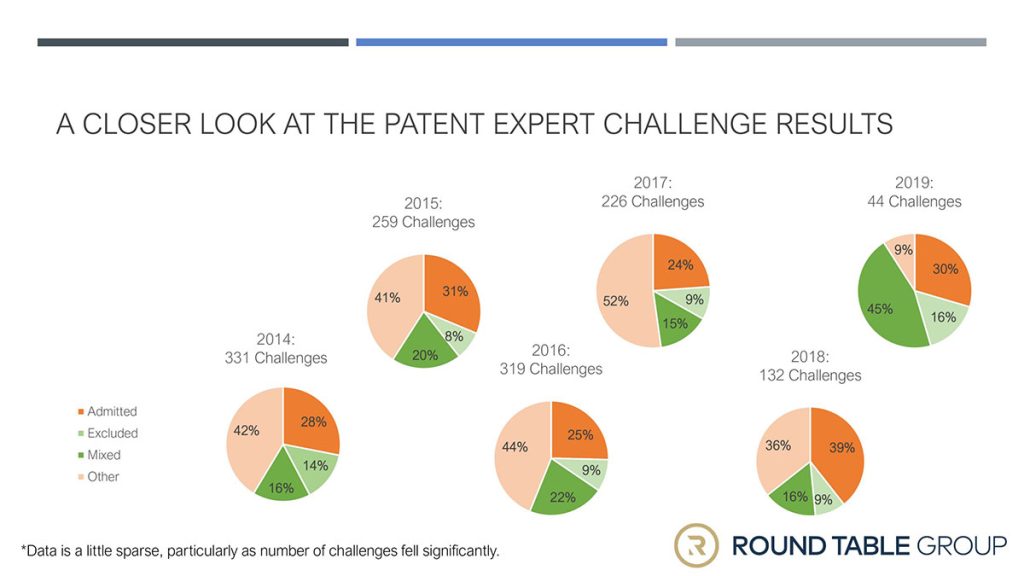

We then drilled down further into the results of these challenges.

As we see, with the exception of an increase in 2016, the trend is steadily downward in almost all categories.

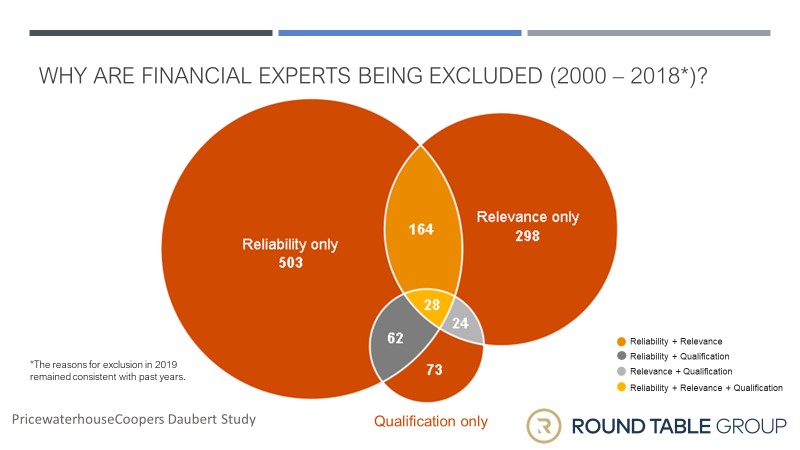

A Daubert study by PricewaterhouseCoopers specifically examined the reasons why financial experts were excluded in the 19-year span from 2000 to 2018.* PwC used a different methodology to identify these exclusions. They searched written court opinions issued between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2018, using the citation search string “526 U.S. 137” (Kumho Tire v. Carmichael). This search identified 10,546 cases that involved 15,740 Daubert challenges to expert witnesses of all types. As a result, they identified 2,623 Daubert challenges to financial experts between 2000 and 2018.) Of the three most common financial expert types (accountants, economists and appraisers), accountants and economists were the most frequently challenged experts. Out of the 2,623 Daubert challenges to financial experts during that time frame, most often (503 times) the testimony was excluded due only to reliability (or a lack thereof) of the experts’ principles or methods underlying their testimony. Second most frequently due to relevance of the testimony only (298 times). Third, a combination of reliability and relevance (164). Fourth, qualification only (73). Fifth, a combination of reliability and qualification (62). Sixth, a combination of reliability, relevance, and qualification (28). And lastly, a combination of relevance and qualification. And lastly, a combination of reliability, relevance, and qualification (24).

*The reasons for exclusion in 2019 remained consistent with past years.

So, why are expert challenges decreasing faster than the patent docket numbers themselves? There are a number of reasons why this might be the case.

So, why are expert challenges decreasing faster than the patent docket numbers themselves? There are a number of reasons why this might be the case.

For questions about this presentation, or for help locating an expert for your litigation matter, please contact Dan Rubin.